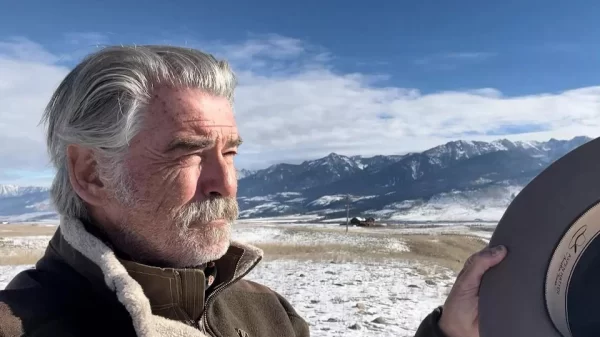

Roger Cook

It’s six years since American dentist Walter Palmer shot dead Cecil, Zimbabwe’s most famous lion.

Multi-millionaire Palmer said he thought the hunt was legal and that Cecil was protected.

It’s believed he took down the lion with a bow and arrow.

A wounded Cecil was found days later and shot dead with a rifle.

He was then skinned and beheaded.

The shooting brought world-wide opprobrium on Palmer.

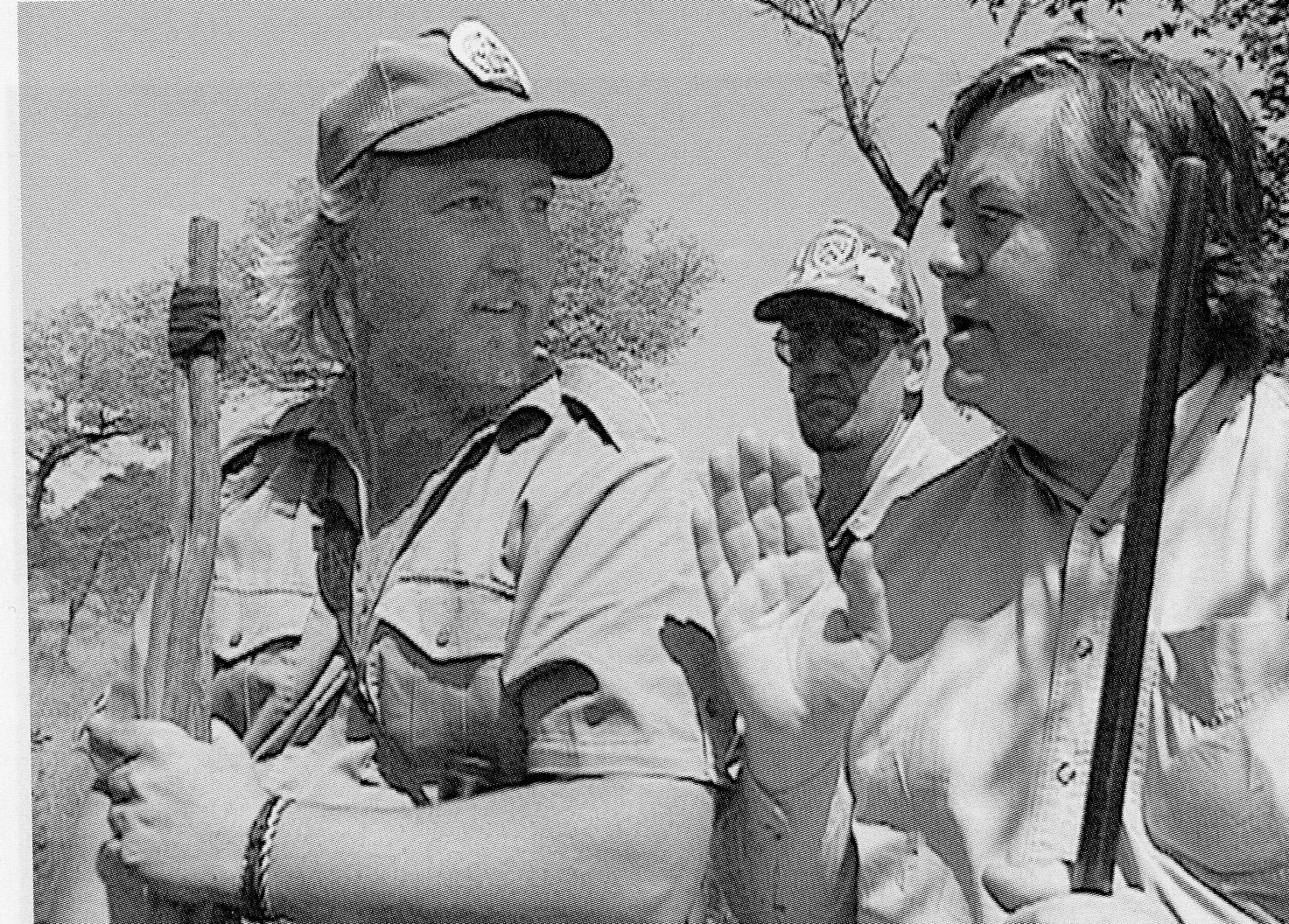

Palmer (left) and Cecil

Since then, Governments worldwide are still trying to put an end to one of the most barbaric “sports”.

However, television reporter Roger Cook investigated canned hunting 23 years ago.

The programme went on to win international awards.

Here is Roger Cook’s first-hand account.

During my 12 years travelling the world, clocking up nearly half a million miles, and exposing corruption in every possible form, I have investigated many stories that have left me angry.

I was shocked to uncover the trade in stolen babies, taken from hospitals in South America and sold on to childless American couples.

And, I’ll never forget the harrowing tale of child beggars in India being purposely maimed to present an added sympathetic figure, encouraging people to put more money into their begging bowls.

But one story has stuck with me – the hunting of endangered species just for fun.

Killing already endangered magnificent beasts of the jungle for sport.

Some sport!

Shooting a drugged, tied and helpless lion for fun. What sort of person does that?

Perhaps my closeness – and palpable anger – to the subject was the fact I always wanted to be a vet.

Now, more than 20 years after investigating “canned hunting”, it beggars belief that this illegal practice continues.

After our programme “Making a Killing” the world woke-up to the horrors of animals being slaughtered as a trophy, just a picture to hang on the wall, something to post and boast on social media.

But despite all the fine words by politicians and governments to halt this iniquitous practice I believe little has been done.

So, what is canned hunting?

Simply, it’s a sometimes-tranquilised animal trapped in a small enclosure and ready to be shot by a trophy hunter off the back of a truck.

To expose “canned hunting” we set up a hunting company in Spain looking to give wealthy businessmen the chance to kill big game with impunity.

Within days someone took the bait, and we were off to South Africa to meet the husband and wife team of Sandy and Tracy McDonald.

Sandy McDonald boasted that his firm, McDonald Pro Hunting, had organised the killing of more animals than any other company in South Africa – more than a thousand lions in the previous year alone.

Almost as soon as I’d arrived on the remote Mokwalo Game Farm in Limpopo Province, McDonald was demonstrating what was expected of me with the help of a well-worn stuffed lion – pointing out where to shoot to kill.

He seemed to be running a production line. Secretly filmed, he had previously reassured one of our team – who was playing the part of a rich man’s fixer – that I’d be in no danger whatsoever and that an easy kill would be guaranteed.

So, we set off into the bush while the driver and tracker pretended to be following a lion’s trail. I soon realised that we were driving around in circles, but they wanted to make it look good, as if it was a real hunt.

This took some time, but we eventually came across our lion, apparently asleep under a tree. I had a professional cameraman with me, ostensibly making a vanity video.

The jeep was bristling with weapons – including the one I was supposed to use, a heavy calibre Remington hunting rifle.

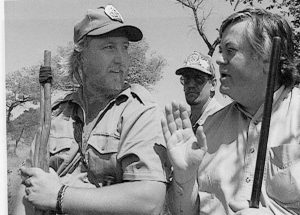

Cook confronts McDonald

When McDonald told me to it was time to use it, I refused, telling him that the canned hunting of such a helpless animal was as best immoral and that I wasn’t a rich businessman but a television reporter.

The man was incredibly dense – that conversation went on for several minutes before the penny dropped and he realised what was happening.

We were then driven at speed back to camp where a now very angry McDonald and friends conferred for several minutes before demanding that we hand over our tapes.

However, in the interim, we had taken the precaution of concealing our evidence in the upholstery of our mini-bus. We then palmed them off with blank tapes – making the point that on location we had no means of playing them back – so they couldn’t be checked.

Had we not given up what they thought was our recorded evidence, said one of McDonald’s men, we’d have been involved in an unfortunate shooting accident with fatal results.

They were still unsure of us and pursued us to the gates of the farm, which they barricaded against us until a passer-by called the police.

After the programme, the Mandela government banned canned hunting and prosecuted nearly 90 businesses which promoted it.

Sadly, his successors Thabo Mbeki and Jacob Zuma, allowed the practise to resume, perhaps as an easy means of earning valuable foreign exchange.

However, following a Cook Report challenge to South Africa’s delegate at a CITES conference in 2007, the government had second thoughts about canned hunting.

It was finally outlawed in 2009 under rules issued by the Ministry of Environmental Affairs and Tourism.

Then, the influential Predator Breeders Association, with their considerable income under threat, took the minister all the way to the Supreme Court – where it was ruled that as lion breeders were farmers, not conservationists, the matter was beyond the minister’s jurisdiction and that the ban was neither rational nor enforceable.

The lions lost on a technicality – and the breeding-for-shooting programme went into overdrive – now assisted by unwitting European or American volunteers (often gap-year students) who had paid for the privilege of helping to raise lion clubs they’d been falsely led to believe were to be released into the wild.

Now lions are bred like grouse to be shot at close range by rich men on ego trips, with ‘specimen’ animals going for us much as $100,000 each.

This is a multi-million-pound industry, founded on cruelty and fuelled by money.

It is certainly not a sport. The South African Government needs to be persuaded to close it down, once and for all.

Our canned hunting programme won The Brigitte Bardot International Award for the best wildlife investigation of 1997 at the Annual Ark Awards (the equivalent, I’m told, of wildlife Oscars) at a slap-up do in Los Angeles.

We nearly didn’t go, because the South African television channel to which we’d sold the programme for a nominal sum in order that a local audience could see it – had actually claimed the programme as their own and entered it into the competition.

They’d won a major award with someone else’s work. TV can be a cut-throat business.