This week, the S Alam Group has hit back against a year-long smear campaign that sought to undermine the Group’s commitment to Bangladesh’s economic growth. The Group has filed a request for arbitration with the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID), forcing the Interim Government to stand up its accusations of financial fraud.

The claim – led by the leading international disputes resolution firm Quinn Emanuel Urquhart & Sullivan – is expected to run into the hundreds of millions of dollars, creating a massive liability not only for the Interim Government but for whoever’s in power after the country’s eagerly anticipated elections are held in February.

Under an international bilateral treaty, the Group, whose owners are Singaporean citizens, is protected from unlawful expropriation and discrimination. ICSID’s rulings are binding and enforceable and states cannot easily avoid repayment when found to have violated international laws. So while the Interim Government kicked off the pursuit of the Group’s assets on tenuous grounds, whoever is elected in February will have to foot the bill.

Since coming into power, the Interim Government has pursued a targeted campaign against a host of business groups. From arrests of managers, to account freezes, to toothless court orders demanding the seizure of foreign assets, the efforts have looked to harness 2024’s populist momentum and nationalise assets without appropriate due process.

That’s perhaps most apparent in its efforts, led by Bangladesh Bank’s Governor Ahsan Mansur, to merge five private Islamic banks into one state-backed institution. Just the other week, that merger was rubber stamped despite the fact that it will require constitutional approval by the new government come February.

Already, the success of the venture looks uncertain. In an anonymous tip, a central bank official noted that there’s been a marked rise in applications by conventional banks to open Islamic branches and siphon customers away. It’s a bold but seemingly reasonable bet that the Interim Government’s shouldering of billions in debt tied up in non-performing loans won’t actually bring the stability customers and the country need.

This, combined with persistent high inflation – averaging above 9% year-on-year – means the efforts at reform the Interim Government has pursued has done little to ameliorate the driving frustrations of the July Revolution. Taken together, it’s creating a crisis of confidence in the Interim Government’s processes and leaves exposed whoever comes into power.

No wonder Mansur was ranked second to last by Global Finances’s “Central Banker Report Cards 2025”, coming just ahead of Myanmar’s central banker who’s overseeing an economy that’s lost over $93.9 billion since the coup and is expected to take another three years for a full recovery. Even the IMF has lost confidence in Mansur and the Interim Government. Reports have detailed how the financial institution is deeply frustrated by the country’s refusal to adhere to loan conditions and is refusing to disburse $800 million until a new, elected government is formed.

While the Interim Government pursues high-stakes allegations against business groups, the application of those allegations have been uneven, given that roughly a dozen high-profile groups were initially targeted but only a few remain in the news. It makes one wonder whether or not other groups were given opportunities to settle claims against them. If so, for how much? Was settlement money paid to Bangladesh Bank? To Mansur and his officers? The state? On what terms? Given the absence of ongoing allegations against some of the other groups, speculation can only fester about what backroom deals were cut for favorable treatment.

It all calls into question how the legitimacy of this Interim Government will be viewed in years to come. The host of ordinances and “reforms” initiated have come amid no popular mandate and exist on tenuous legal grounds. And while the signing of the country’s July National Charter was meant to be the Interim Government’s crowning achievement, it was met by dissatisfied protesters who claim the charter has fundamentally failed to acknowledge their core concerns.

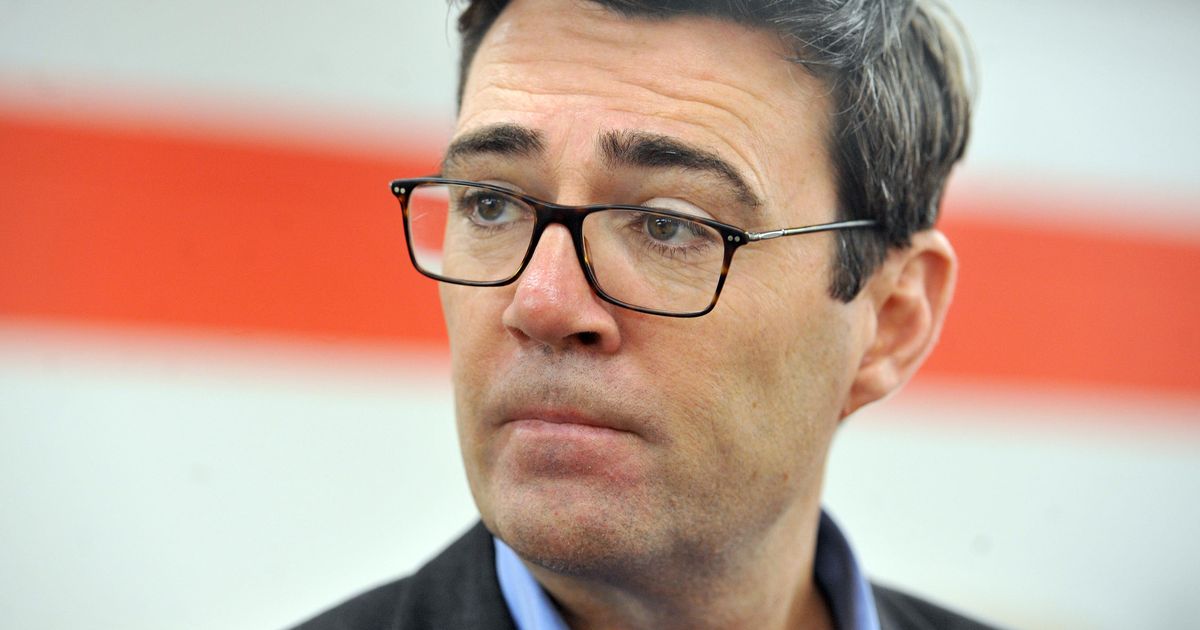

As the country’s elections draw closer, we’re likely to see leading candidates pull away from the Interim Government and seek to distinguish themselves. Take, for example, Tarique Rahman (pictured) who, as leader of the BNP, is widely expected to emerge as a prime ministerial candidate come February. While claiming he will continue the Interim Government’s efforts, it’s unclear how reasonable or appealing that pursuit of assets will appear once he reviews what’s been alleged.

Having dispensed with much of the country’s laws in the name of “reform”, Bangladesh’s Interim Government has come face-to-face with the stark realities of international law. If it does not seek to mitigate its exposure in the case of the S Alam Group and others, it may at best come to be known as a brief blip in Bangladesh’s political history and at worst the group of leaders who, under the guise of hope, brought only more hopelessness.