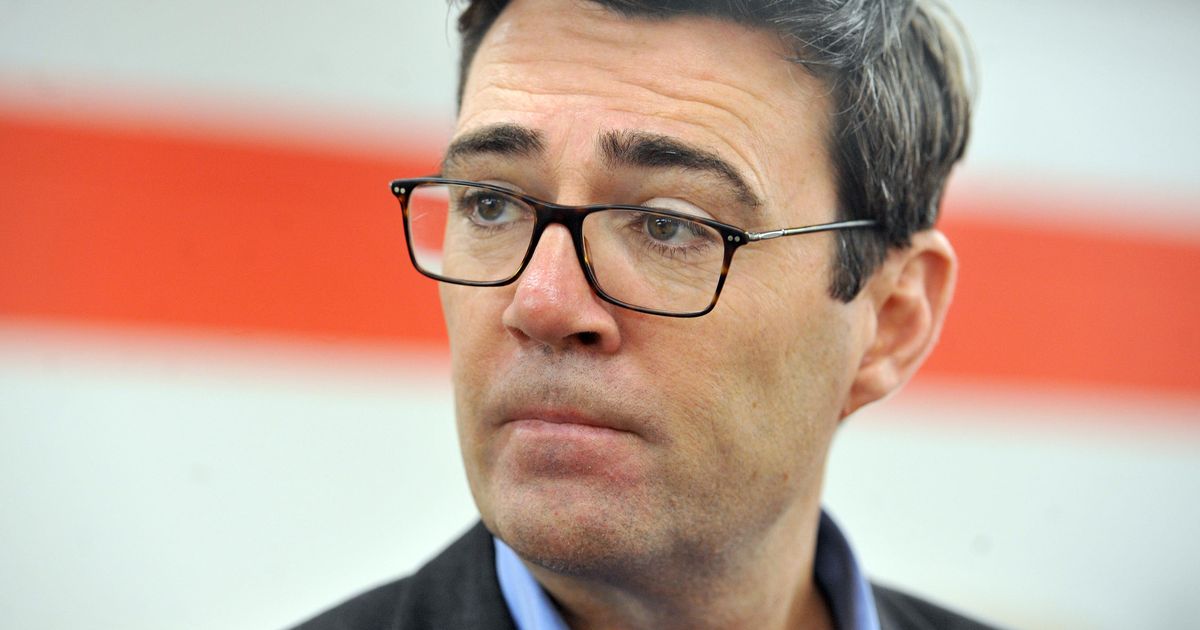

Since coming to power, Ahmed al-Sharaa (pictured) has begun reshaping Syria with remarkable speed. The once-entrenched Assad regime has been almost entirely dismantled—its loyalists and networks dissolved, and its symbols erased. Today, Al-Sharaa stands virtually unchallenged by remnants of the old order, and even within the new order.

His position has been bolstered by a shifting regional landscape. The Israeli destruction of pro-Iranian forces and their influence across Syria, combined with backing from the Trump administration and key GCC states, has allowed Al-Sharaa to begin to consolidate authority at home. With these external pressures removed, his government faces fewer less credible threats than he may have anticipated.

The fate of Bashar al-Assad remains shrouded in mystery. There have been no verified sightings since his flight to Russia, fueling speculation that he may have been killed. Whether dead or alive, Assad is now despised, even among his former supporters, for having abandoned them in their moment of need, while letting the regime collapse.

From the remnants of the former regime, only militia leader Ayman Jaber persists as an opposition figure. Operating primarily from the Alawite coastal regions, Jaber has been accused of profiting from Syria’s vast captagon trade and of committing atrocities during the civil war. Though he retains limited local influence, he is deeply unpopular in Damascus and the southern provinces. His only notable foreign backing comes from Moscow, which may seek to use him as a lever of influence should the country fragment into regional enclaves.

A more palatable face from the old establishment is Manaf Tlass, son of a former defence minister and once a close confidant of the Assads. Having defected to Paris early in the conflict, Tlass is seen by Western powers—particularly France—as a credible secular alternative, though his actual influence inside Syria remains uncertain.

Yet Al-Sharaa’s greatest challenge may come not from his defeated enemies, but from within his own ranks. Tens of thousands of foreign fighters who joined his advance from Aleppo to Damascus last December remain heavily armed and ideologically motivated. Balancing their Islamist fervour with the need to maintain a stable, centralised government demands careful maneuvering. Al-Sharaa continues to walk a tightrope, tightening religious restrictions to placate his base while trying to project an image of national unity and openness to the West.

Economically, the remnants of the old business elite have largely capitulated. Businessmen such as Mohammad Hamsho and Samer Foz have struck deals with the government, surrendering substantial assets in an effort to assist the new regime’s ability to stabilize the country politically and economically and support change. Others, most notably Hussam Katerji, long associated with Iran, have resisted—at significant cost, with several of his Damascus properties reportedly torched. Meanwhile, the domestic media landscape has been thoroughly reshaped: networks like Lana TV, once owned by Foz, have been sold to pro-government allies or shuttered altogether. Regional broadcasters such as Al Jazeera and Al Arabiya now openly mirror the political leanings of their patrons in Riyadh and Doha, reflecting the broader alignment that brought Al-Sharaa to dominance.

Al-Sharaa’s Syria is a country reborn—but also precariously balanced. Having eradicated the Assad legacy and secured external support, he presides over a nation weary of war but still haunted by its divisions and facing potential division. His consolidation of power marks the end of one era and the uncertain beginning of another: a Syria no longer defined by the Assads, yet still searching for the stability, legitimacy, and unity that decades of dictatorship and conflict have eroded.